Taranto could have been one of the most beautiful cities in Southern Italy, a serious competitor to Naples and Palermo, but was condemned to a long decay. The ILVA steelworks controversy is one of the worst national scandals we ever had, and still without an end in sight. But a visit to Taranto’s historic centre would be a remarkable tribute to a much neglected city.

Taranto lies between the Mar Grande, a bay in the Gulf of Taranto, and the Mar Piccolo, famous for its mussel cultivation. Known as the city of two seas, its borgo antico, the historic old town, is located on a small island is connected to the mainland by a road bridge on each of its northern and southern ends.

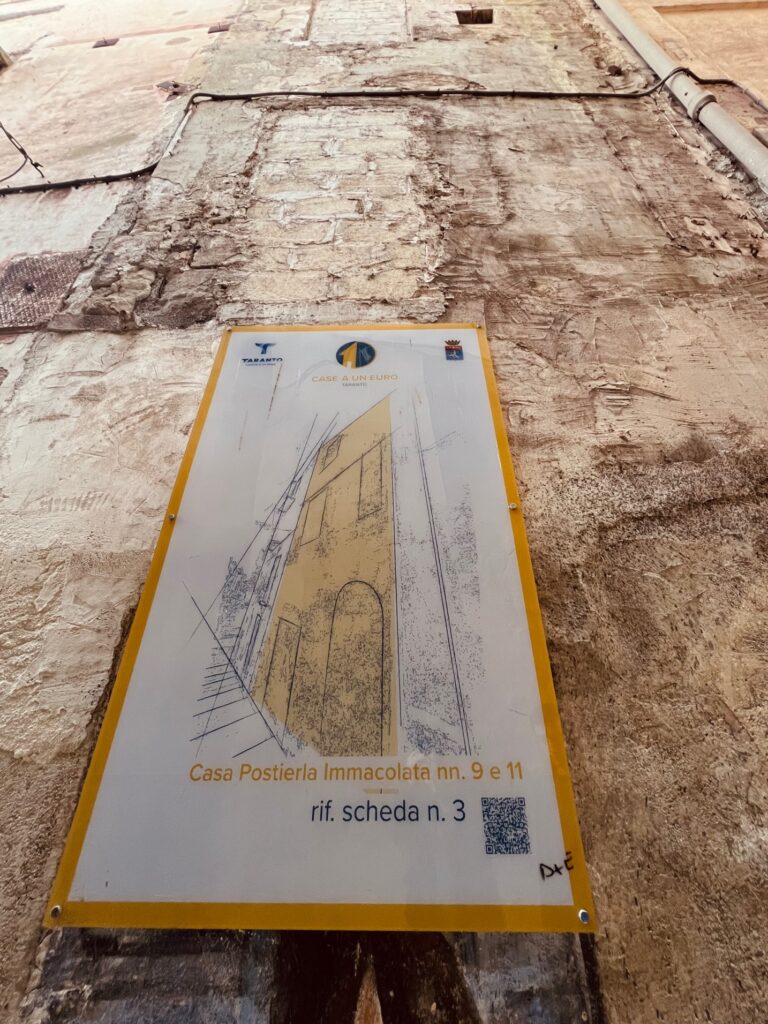

The piers of Taranto’s porto vecchio are lined with fishing boats. Sitting behind is la Città Vecchia, Taranto’s historic centre. A maze of small shops and restaurants, where whole houses can be bought for 1€. Raw and gritty, yet breathtakingly authentic.

Fewer tourists visit the city of Taranto. The fume-belching chimneys of the neighbouring steel processing plant, a testament to Taranto’s troubled recent history, continue to cast their shadow. In the first eight months of 2024, according to data from Pugliapromozione, only the BAT province (Barletta-Andria-Trani) saw fewer tourist arrivals than Taranto. The city registered half as many visitors as Brindisi, a third as many as Bari, and only a fifth of those seen in Lecce. Among Puglia’s municipalities, Taranto ranks 20th for visitor numbers – one third fewer than Nardò.

Only this month (March 2025) we received a message, including this:

“…We had decided [to miss out] Taranto because we’d read some comments online that described it as very industrial and synonymous with poverty, filth, and ruins…”

To overlook Taranto would be an oversight. For those who do visit, the experience is unique, as if stepping back in time. Rundown and poor? Perhaps. But be in no doubt. Taranto’s old town is full of character and full of life. Real, lived life. It may be a world apart from Puglia as represented by Alberobello. But Taranto is real, essential and unmissable Puglia. To miss it out is to miss out.

Spartan Taranto

The earliest settlements in the area were established by the Mycenaeans, a civilization that flourished in Greece from the 15th to the 12th century BCE.

The Spartans first came to Taranto in the 8th century BCE when they established Sparta’s only colony on the island of Taras (present-day Taranto). Over time, Sparta Taras (named after Neptune’s son) became a thriving and influential city, known for its wealth and cultural achievements. The Spartans who lived there became known as the “Tarasii,” and were highly respected for their military skills and devotion to their city.

Numerous artifacts and monuments that tell the story of Taranto’s Greek past remain, including a row of Greek columns standing near the water.

All roads lead to Rome

Despite its success, Sparta Taras eventually came into conflict with the Roman Republic. In 272 BCE, the Romans conquered the city and made it a part of their empire. Under Roman rule Tarentum became an important port for the Roman Empire, connected to Rome by the Via Appia.

The Via Appia, also known as the Appian Way, was a Roman “superhighway” built in the 3rd century BCE that stretched from Rome to the southern part of Italy. It was one of the most important roads in the Roman Empire, serving as a major artery for trade, military communications, and other forms of travel.

The section of the Appian Way in Taranto was built in the 2nd century BCE and was used for hundreds of years until the decline of the Roman Empire. Notable for its well-preserved state, many of the original features of the road are still visible today.

Since Roman times the city has been a key port for trade and shipbuilding. The port was later named “La Arsenale” (and the city is still a major military base and home to the Arsenale Militare Marittimo Taranto).

From Ancient age to Late Modernity

During the Middle Ages, Taranto was ruled by a series of different powers, including the Byzantines, the Lombards, and the Normans.

In the 14th century, Taranto became part of the Kingdom of Naples, and it was during this time that the city experienced a period of prosperity and cultural growth. The Renaissance and Baroque periods also saw significant cultural and artistic development in Taranto, with the construction of numerous churches (witness the old town’s main cathedral dripping in marble), palaces, and other important civic buildings.

In the 19th and 20th centuries, Taranto underwent rapid industrialization, becoming an important centre for the production of steel and other metals. And from its glorious past, Taranto was condemned to a long decay.

Horrible History

Beyond the island that holds Taranto’s old town, the Via Appia runs alongside the steelworks that blight Taranto’s landscape and reputation.

The ILVA steelworks is a large industrial complex, one of the largest steel production facilities in Europe. It was founded in 1965 under the name Italsider and has undergone several expansions over the years. The complex – one of the world’s largest iron and steel works – includes a number of facilities for iron and steel production: coke ovens, blast furnaces, steelmaking furnaces, and rolling mills.

The steelworks has a long history of environmental controversies. It has faced legal challenges related to the emission of pollutants and the management of hazardous waste and became the subject of a national scandal involving allegations of environmental crimes, corruption, and mismanagement.

The scandal began in 2012, when the Italian government seized control of the company and placed it under special administration due to concerns about the environmental impact of its operations. Subsequent investigations have revealed that the company allegedly engaged in illegal dumping of toxic waste and released high levels of pollutants into the air and water, leading to serious health problems for local residents. There have also been allegations of corruption within the company, including the use of false invoices to avoid paying taxes.

The ILVA scandal has received widespread media attention in Italy and has had significant political and economic consequences. The company has faced numerous legal challenges and has been the subject of ongoing efforts to clean up its operations and address the environmental damage it has caused. In May 2021 the plant’s former owners, Fabio and Nicola Riva, were handed lengthy prison sentences for their roles in allowing it to contaminate the city.

But its legacy reaches further. Studies have suggested that high cancer rates, especially among children, and other health problems are attributed to air pollution from elevated emissions of dioxin from the ILVA steelworks.

Production continues to this day and the steelworks still provide jobs for the people of Taranto.

Reviving the Heart of Taranto

For the better part of three decades, Taranto’s old town lay in near-total abandonment. Once the vibrant heart of the city, its winding streets and historic buildings were gradually emptied as residents moved away in search of better housing, spurred by the economic boom brought by heavy industry. As new jobs emerged, so did new aspirations—and with them, a preference for more modern, comfortable homes outside the ancient centre.

By the early 1990s, the population of the città vecchia had dwindled to a fraction of its former size. Most of the grand old buildings had become derelict shells, and large parts of the quarter stood silent. A significant portion of the real estate, then as now, remained in municipal hands—unused and unmaintained.

Now, however, change is underway. New regeneration projects aim to transform the old quarter into a living part of the city once more—vibrant, inhabited and open to the world. These efforts aren’t just cosmetic. Local leaders see the revival of the città vecchia as a catalyst for broader change. By unlocking the potential of Taranto’s cultural and historical assets, they hope to drive a new chapter of sustainable growth and pride in place.

It’s not just the old town getting attention. A striking €36 million redevelopment of the city’s Mar Grande waterfront is currently underway—a bold, contemporary gesture to complement the restoration of the past. The plan is to stitch Taranto’s three urban districts back together via an uninterrupted sea-level promenade, dotted with services, access points, and open spaces for public use. To reacquire and implement the relationship between the city and the sea. It will also link the city’s new cruise terminal with the base of the imposing Aragonese walls that ring the old city, offering arriving visitors a dramatic new vantage point on Taranto’s layered history.

Together, these efforts point towards a city determined not only to preserve its past, but to reimagine its future. With unemployment on the rise again – now at 13.3% compared to the regional average of 12.2% and a national figure of 8.1% – there is a real need so to do.

The beauty underneath

Taranto’s landscape is still dominated by the smokestacks that push up from the industrial expanse, billowing black fumes and white plumes of condensed steam, and by huge hangar-like buildings that house the ash and steel particles.

Yet – and yet – we are drawn to the beauty underneath. We did not see it at first. Not even on our second and third visits.

Our love affair with Taranto’s old town started with cozze: mussels. La cozza tarantina is unlike any other we have tasted. Tarantina mussels benefit from the unique conditions of the bay in which they are cultivated. Oxygen rich underwater springs flush into an inner basin which already has a higher salinity. This favours and flavours the plankton, plumping up the mussels with their distinctive taste.

Having tasted them cooked in a variety of dishes, but also raw and steamed in a simple broth, they have become a taste obsession. To the extent that we will only order mussels on the menu if they come from Taranto.

Then there’s the old town itself. Much of it dilapidated. Raw, gritty and authentic. Scattered on its edges, a few fine restaurants with exceptional seafood and fish. Fresh and local. So local, you can probably follow the trail of water drips to the boardwalks along the quayside where it was bought from the fishermen who landed it.

Within its winding alleyways new art galleries, wine bars and pop-up spaces are appearing alongside the street art and rusted street signs.

Culture is coming. A fuel that doesn’t pollute. And with it the slow gentrification that drags the old into the now. Taranto truly is a paradox, a city of contrasts.

Our Taranto hit list

Eat

Ristorante Al Canale | fish and seafood restaurant popular with the business community. Bright and airy, overlooking the channel between la Città Vecchia and downtown Taranto. A flawless lemon scented insalata di mare served hot in a lemon brodo impressed us.

Ristò Fratelli Pesce | a busy fish and seafood restaurant at the northwestern end of the old town island, not too far from the Porta Napoli bridge. Seafood pasta dishes are highly recommended, as is booking. Via Porto, 18 (+39 339 818 2010).

La ringhiera pizzeria Di Michele Ruggiero | opposite Ristò Fratelli Pesce. We walked in when we couldn’t get a table at Fratelli Pesce, and were pleased we did. Recommended for raw and cooked plates of seafood. Piazza Sant’Eligio, 12 (+39 320 710 6301).

Gente di Mare Trattoria | Cucina di Pesce a Taranto – fish and seafood restaurant. What can we say. Excellent, and popular with locals. It was full for Sunday lunch, always a good sign. Via Garibaldi, 254. (They also have a restaurant at the other end of the borgo antico which we haven’t tried).

See

MArTa – National Archaeological Museum of Taranto

A world class museum, considered one of the most important archaeological museums in Italy, particularly in the study of the ancient Magna Graecia (Southern Italy and Sicily colonised by Greeks) civilisation.

The museum houses a vast collection of ancient artifacts from the area, including items from the Paleolithic and Neolithic periods, as well as from the Bronze Age, the Iron Age, and the classical period.

One of the highlights is the collection of artifacts from the ancient city of Taras, which was founded in the 8th century BCE by Greek colonists and was one of the most important cities in ancient Magna Graecia. Visitors can see a variety of pottery, jewelry, and other objects from the city, including several bronze and marble statues and the famous “Taranto Bronzes,” a group of bronze objects that were discovered in the city in the early 20th century.

It is said to house the finest collection of Hellenic gold out side British Museum.

MArTA also contains a collection of Roman artifacts including sculptures, inscriptions, and architectural elements, as well as several mosaics. One of the most interesting pieces on display is the mosaic floor from the Roman Villa which is located in the ancient city of Taranto.

Overall, the National Archaeological Museum of Taranto provides a fascinating glimpse into the rich history of the region and the various cultures and civilizations that have inhabited it over the centuries. It is also an interesting cultural institution that tells the story of the ancient Greek colonization, the Messapic civilization and the Roman civilization in southern Italy .

A medieval fortress built in the 15th century by the Aragonese, a powerful maritime kingdom that controlled much of southern Italy and Sicily at the time.

The fortress is made of a large, rectangular main tower and three smaller towers. The main tower, also known as the keep, is the tallest and most imposing part of the castle and offers a panoramic view of the city and the sea. The castle also has a large courtyard and several rooms, including a chapel and a prison.

The castle played an important role in the history of Taranto and the surrounding region, serving as a military stronghold, a royal residence, and a prison over the centuries. It was also an important symbol of the Aragonese’s power and control over the area.

The Castello Aragonese has undergone several renovations and restorations over the years, and it is now open to the public as a museum. Visitors can explore the castle’s various rooms and towers, and learn about its history and the role it played in the region.

Tours are led by the Italian Navy.

Basilica Cathedral of San Cataldo, Taranto

The Cathedral of San Cataldo, located in the heart of Taranto’s old city, is not only the oldest Romanesque cathedral in Puglia but also a fascinating repository of overlapping architectural styles and artistic expressions that span more than a millennium. Its history reflects Taranto’s role as a key Mediterranean city — Byzantine, Norman, Angevin, and Spanish influences all converge here, layered into one of the most complex ecclesiastical structures in southern Italy.

The cathedral is 84 metres long and 24 metres wide, with a central nave, two aisles, and a single-aisled transept. Columns of various styles and reused capitals divide the naves. The side aisles house chapels, including the Chapel of Saint James and the Chapel of Saint Martha, both linked to local religious traditions and the discovery of relics.

Origins and Early Structure

The origins of the cathedral are rooted in late antiquity. A paleochristian church, possibly dedicated to Santa Maria, stood here by the 7th century — its existence evidenced by a letter from Pope Gregory the Great. This early church was likely demolished by Bishop Drogone in the mid-11th century to make way for a more dignified cathedral. According to the Historia by Berlengerio and a text known as the Ufficio Cataldiano, the body of San Cataldo was discovered during the foundations’ excavation.

Under Norman rule, Drogone likely initiated the transformation of the existing Greek-cross plan church into a Latin-style basilica with three aisles, demolishing one of the transept arms and possibly the subterranean crypt. The capocroce and crypt, however, predate this intervention and show signs of a free-cross plan that may once have formed a standalone sanctuary dedicated to San Cataldo. Professor Pina Belli D’Elia has demonstrated the Byzantine character of these lower levels, showing their structural role in supporting the weight of the upper church.

The Nave and Columns

The nave is defined by a striking irregularity that reveals the pragmatism of medieval construction. Built hastily with salvaged materials from Roman, Late Antique, Byzantine, and medieval buildings, the columns and capitals reflect remarkable variety:

- Right nave columns: feature primarily Corinthian capitals, reused or newly carved in imitation. Notable examples include a capital with pomegranates (3rd column), and a composite late Byzantine capital made from two segments (5th column).

- Left nave columns: feature primarily figurative capitals from the late 11th century, incorporating influences from Byzantine, Islamic, and Western (Lombard, Carolingian, Ottonian) art. Subjects include acanthus foliage, peacocks, putti, lions’ heads, ram protomes, and symbols from early Christian iconography.

Many of these columns, including granite shafts and cipollino marble fustes, are identical in dimension and may originate from Jewish religious buildings. One column even contains engraved Hebrew units of measurement — the palm, cane, and perch.

The capitals of the left aisle are especially significant. Their iconography shows clear links to Byzantine and Islamic motifs, such as the double-headed eagle and the perfumed sphere. These were executed by a local workshop that anticipated the Romanesque style by fusing regional heritage with imported Norman tastes.

The Ceiling

The lateral aisles are roofed with wooden trusses, while the central nave is crowned by a gilded walnut coffered ceiling commissioned by Archbishop Albornoz after a fire in 1635. Completed under Archbishop Stella, it features carved wooden statues of Saint Cataldus and the Immaculate Virgin, as well as the coats of arms of both bishops.

Presbytery and High Altar

At the end of the nave, stairs flank the entrance to the crypt and lead up to the presbytery. The current high altar, commissioned in 1784 by Archbishop Capecelatro, replaced an earlier altar containing the relics of San Cataldo, later transferred to the adjacent Cappellone.

Above the altar stands a ciborium supported by four porphyry columns with composite capitals. It was constructed under Archbishop Caracciolo to replace the earlier ciborium now in the baptistery. The pyramidal canopy features the four Evangelists in white marble, along with Caracciolo’s heraldic devices. Overhead, the Byzantine-style dome is frescoed with Evangelist scenes by Domenico Torti.

Behind the altar, in the deep apse, is a walnut choir commissioned by Archbishop Stella, replacing a 15th-century version by woodworker Bernardino Morelli.

The Cappellone of San Cataldo

The third apse, the Cappellone di San Cataldo, is unexpected and quite extraordinary. A masterpiece of Baroque opulence, the chapel remains an unparalleled example of Baroque art in Puglia due to its integrity, originality, and quality. Commissioned in the mid-17th century by Archbishop Tommaso Caracciolo (who served for 25 years), the chapel was conceived as a fitting sanctuary for the relics of Taranto’s patron saint.

This richly decorated chapel contains the saint’s relics and includes an elliptical space built over an older 12th-century structure. Its marble-clad interior features statues by Giuseppe Sanmartino, inlaid altars, and a silver statue of Saint Cataldus. Precious marble, mother-of-pearl, and lapis lazuli adorn its interior. Its centrepiece is a grand dome frescoed with the Glory of San Cataldo by Paolo de Matteis painted in 1713, depicting scenes from the saint’s life and miracles.

The Cappellone consists of two parts: a quadrangular vestibule and an elliptical chapel. The vestibule corresponds to the ancient chapel built in 1151 by Archbishop Giraldo to house the relics of Saint Cataldus.

Architecture and Marble Decoration

The identity of the architect is unknown, though the design shows affinities with the Neapolitan school of Cosimo Fanzago. The marble decoration began under Archbishop Sarria (1665–1682), using largely recycled marble from classical structures. The walls are segmented with pilasters and niches, decorated with shells, vegetal motifs, precious stones, and inlays of lapis lazuli and mother-of-pearl.

The High Altar

Giovanni Lombardelli designed the high altar, which is a masterpiece of Neapolitan inlay. It displays the city and chapter’s coats of arms, as well as symbolic white disks containing flower vases and a star. Putti were added later under Archbishop Pignatelli. The relics of Saint Cataldus lie within, visible through a lateral window.

The niche above the altar is enclosed by silver doors made by an anonymous Neapolitan silversmith in 1793. They protect a statue of Saint Cataldus, realised in 1984 by Orazio del Monaco using 35 kg of silver donated by Taranto’s goldsmiths. It replaces a 19th-century statue by Vincenzo Catello, itself a replacement for a 15th-century full-figure sculpture derived from the melted silver ark originally commissioned by Archbishop Giraldo in the 12th century.

Sculptures by Sanmartino

The Cappellone houses six major statues by Giuseppe Sanmartino (1720–1793), Naples’ most celebrated sculptor of the 18th century. He worked in Puglia from 1751 to 1790 and is known for his Veiled Christ in the Cappella Sansevero.

Two additional statues at the entrance (Saint Sebastian and Saint Mark) are by Giuseppe Pagano (1804). Two more flanking the altar (Saint Peter and Saint John the Baptist) are anonymous works from the late 16th to early 17th century.

Statues of the Cappellone

The addition of statues to the pre-designed niches of the Cappellone occurred later. Six of these sculptures are considered genuine masterpieces, while four others — stylistically inconsistent — were added simply to fill the remaining small niches following the death of the great Neapolitan sculptor Giuseppe Sanmartino, to whom the original commissions had been entrusted.

At the sides of the entrance stand two neoclassical statues by Giuseppe Pagano, dated 1804:

- Left: Saint Sebastian

- Right: Saint Mark

Flanking the altar are two earlier statues, of uncertain origin and date (late 16th to early 17th century):

- Right: Saint Peter

- Left: Saint John the Baptist

The remaining six statues are by Giuseppe Sanmartino, one of the most gifted sculptors in 18th-century Naples, and are placed in the central wall niches.

Left wall (from the entrance):

- Saint Teresa

- Saint Dominic

- Saint Philip Neri

Right wall (from the entrance):

- Saint Irene

- Saint Francis of Assisi

- Saint Francis of Paola

These statues were commissioned and executed during the episcopate of Archbishop Mastrilli (1759–1777). However, their acquisition was made possible by a bequest from an earlier archbishop, Isidoro Sanchez de Luna, who donated 1,500 ducats to the cathedral for this purpose. His coat of arms is placed beneath the brackets of Saints Francis and Dominic.

Giuseppe Sanmartino

Born in Naples in 1720, Sanmartino became famous in 1753 for his Veiled Christ in the Cappella Sansevero — a work of extraordinary virtuosity. His versatility enabled him to work in marble, stucco, terracotta, and also to design silver and wooden statues.

His work in Puglia began in 1751 with statues of Saint Michael the Archangel and Saint Joseph for the cathedral of Monopoli. Between 1754 and 1759, he created the six statues for the Cappellone di San Cataldo in Taranto. He also sculpted the figures of Abundance and Charity for the high altar of the collegiate church in Martina Franca, as well as works for Foggia’s cathedral (1767). His final known works in Puglia are the statues of Saint Giovanni Gualberto and Saint Joseph, now in the vestibule of the Cappellone (1790).

Sanmartino’s influence in Puglia was significant, and altars in the presbytery and transept of the collegiate church in Maglie are attributed to his school. Stylistically, his work shares traits with Mauro Manieri — especially in facial expressions — and also echoes the lively, emotionally charged figures seen in the Church of San Giuseppe dei Ruffi in Naples.

Even works such as the holy water fonts and reliefs in the cathedral of Presicce (1778), and the statue of Saint Gregory in Manduria’s cathedral (carved in wood by Michele Trillocco), suggest his lasting artistic legacy. His followers include Angelo Viva, who sculpted the statues of Faith and Hope for Lecce Cathedral and the Immaculate Virgin for the Church of Saints Peter and Paul in Galatina.

Although Sanmartino’s style, full of pathos and dramatic gesture, was eventually overtaken by a more composed neoclassicism, his emotional, dynamic approach gave way to more academic religious sculpture by the early 19th century. This later tradition culminated in highly standardised papier-mâché figures popular well into the 20th century.

Frescoes by Paolo De Matteis

With the arrival of Archbishop Giovan Battista Stella in 1713, the Cappellone’s rich marble décor was finally completed. Stella commissioned Paolo De Matteis to fresco the dome and drum with the Glory of Saint Cataldus and episodes from his life.

At the base of the dome, above the altar, De Matteis painted Stella’s coat of arms. Opposite is a cartouche signed Paulus de Matthaeis P. (pinxit). The drum features seven scenes from the saint’s life:

Right of the altar:

- Saint Cataldus receives a divine command to go to Taranto while praying at Christ’s tomb in Jerusalem

- Saint Cataldus cures a mute

- Saint Cataldus exorcises a possessed woman

Left of the altar:

4. Saint Cataldus resurrects a worker buried by rubble

5. Saint Cataldus resurrects a child brought by his mother

6. Saint Cataldus restores sight to a blind man

Centre, opposite the altar:

7. Saint Cataldus preaching to the people of Taranto

The dome depicts the Glory of Saint Cataldus. In a sky filled with swirling clouds, angels encircle Christ and God the Father, while the Virgin Mary welcomes Saint Cataldus into glory. Saints in adoration, mostly wearing Franciscan and Dominican habits, occupy different cloud levels:

- Right: Saint Joseph, Saint Catherine of Alexandria, Saint Mark, Saint Roch, Saint Sebastian, Saint Lawrence, Saint Paul, Saint Charles Borromeo, Saint Anthony

- Left: Saint Peter, Saint John the Baptist, Saint Dominic, Saint Francis of Paola, Saint Francis of Assisi, Saint Teresa of Ávila, Saint Gaetano, and Saint Nicholas of Bari

Chapel of the Blessed Sacrament

To the left of the altar is the Chapel of the Blessed Sacrament, originally dedicated to Saint Agnes. It was transformed into a Baroque space beginning in 1657, housing the confraternity of the Blessed Sacrament and Monte di Pietà.

The altar, completed under Archbishop Mastrilli (1775), includes lapis lazuli inlay and putti similar in style to Sanmartino. Paintings by Giovanni Molinari include:

- The Fall of Manna

- The Multiplication of Loaves and Fishes

- The Last Supper (a cropped canvas, showing ten apostles)

- Madonna della Salute (attributed to Antonio Verrio, echoing Roman Marian icons)

The Crypt

Beneath the nave lies a three-aisled crypt, accessed via side staircases. Originally hypogeal, its thick walls support the church above. Belli D’Elia argues convincingly for a Byzantine origin, based on window design and structural integration.

The crypt’s layout mirrors the capocroce above and features reused Roman columns with slab capitals. Groin vaults are later additions. Excavations in 1931 confirmed its floor lies beneath the Roman and Byzantine street levels.

Frescoes in the Crypt

Restored in 1985, the crypt’s frescoes include:

- A palimpsest of Saint Cataldus over earlier images of Mary Magdalene and Saint Mary of Egypt

- A Madonna and Child enthroned

- Saint Anthony Abbot with a pig and the letters “IU”

- Four headless bishops

- A diptych of the Madonna and Saint Peter

- Saint Nicholas and Saint Anthony of Padua

These paintings reveal a stylistic evolution from late Byzantine to the “Angevin current,” which blended Western realism with Eastern motifs. The decorative elements — shells, rosettes, floral bands — suggest connections with crypts in Veglie and Santa Maria del Casale in Brindisi.

Conclusion

The Cathedral of San Cataldo in Taranto stands as a monumental synthesis of Puglia’s religious, artistic, and architectural history. From the reused Roman columns to the Byzantine crypt, the Baroque Cappellone to the Neapolitan frescoes, every corner of this cathedral tells a layered story of faith, adaptation, and artistic ambition. It is not just a sacred space but a testament to the enduring cultural crossroads that defines Taranto — and indeed, Puglia itself.

The chapel continues to captivate visitors, just as it once evoked mixed reactions from 18th-century travellers. While some, like philosopher George Berkeley, found it awe-inspiring (“the oval inlaid chapel is unsurpassable”), others, including Sir Henry Swinburne (“the chapel of the patron saint has been decorated at the expense of almost all the monuments of the ancient city”), lamented its Baroque excesses.

The Cathedral is open to the public free of charge. A panoramic view of Taranto’s borgo antico can be enjoyed from the cathedral’s rooftop terrace (for which a 2€ fee is charged).

The Salinella neighbourhood

Taranto amazes us simply because here the ugly becomes beautiful. The Salinella neighbourhood buzzes with life on market day. Brutal tower blocks rise up all around. But it is vibrant, full of noise, full of life.

Do

Stroll down the Via Duomo. The Cattedrale San Cataldo is much grander than its surroundings, steeped in marble.

Walk along the Via Garibaldi and port from the swing bridge at the southern end of the old town to the Porta Napoli bridge.

Taranto’s swing bridge, officially known as the “Ponte Girevole” or “Rotating Bridge,” is a unique and iconic feature of the city.

The bridge was designed and constructed in 1907, by the engineer Alberto Paleari. The central section of the bridge can rotate 90 degrees to allow boats and ships to pass through the narrow strait. The rotation mechanism is operated by an electric motor, which was a technological innovation for the time of the construction. The bridge’s rotation can take about 8 minutes.

The bridge’s design is a combination of functional and aesthetic. The steel structure has a simple, industrial appearance, but it’s also decorated with elements of Art Nouveau and Liberty Style, which are characteristics of the period of the construction.

Although we focus on the old town, it is interesting to contrast it with “modern” downtown Taranto. A busy and restless city. If you have the time walk from the Giardini Piazza Garibaldi to Piazza Maria Immacolata.

Sense and sensitivity

Taranto’s old town is raw and gritty. As is obvious from the very dilapidated state of many of the buildings, this is an economically challenged part of Taranto. A slow gentrification of sorts is coming. The port is a busy working one, where fishing boats jostle for space. But we hear anecdotally that fish is not the only thing landed.

Be aware of your surroundings and of the circumstances of those who live there. We suggest parking in the car park at Corso Vittorio Emanuele II, in the downtown area of modern Taranto around the Giardini Piazza Garibaldi or nearby.

During the day if you are wondering around the maze of streets off the Via Duomo in the northern section between the cathedral and the Piazza Fontana we recommend keeping your phone in your pockets. At night we recommend sticking to the Via Duomo or the main roads that run around the old town (Via Garibaldi and Corso Vittorio Emanuele II).

However this advice is offered by way of an abundance of over caution for naive and unseasoned travellers. Please do not let it put you off visiting a wonderful and unique part of southern Italy.

Stay.

Hotel L’Arcangelo

We stay at the Hotel L’Arcangelo, ideally located on Piazza Fontana at the northern end of Taranto’s borgo antico. It is still our top choice – we have stayed there three times. The hotel is stylish, clean and bright with spacious rooms. We had one of the friendliest welcomes we have experienced in Puglia, with cake and a glass of sweet wine, a symptom of a hotel bursting with pride. Pride in their city and in the service they provide to their guests.

Our first room, the camere delux – a corner room with dual aspect – was our favourite. We preferred it to the suite l’arcangelo and the camere deluxe con terrazze e vista mare (with the terrace and sea view). The sea view was negligible!

Read about our first stay at Taranto’s Hotel L’Arcangelo and why we liked it. As always we paid in full for our stay and received no payment or incentive for our review.

Palazzo Matà Boutique Hotel

We had a mixed experience staying here. It needs a more thoughtful breakfast service, but provided good value on whole, with one significant exception – the luxury “suite” which turned out to a big disappointment.

The location was great. We booked three rooms. The superior double room and the deluxe room were good value at €138. Each had a generous sized room with a well proportioned bathroom, and walk-in shower. The deluxe double room with sea view and hot tub at €210 was terrible value, especially compared with the other two rooms we had. It turned out to be a small, cramped room called Bolle “suite”, which certainly was not a suite. It had a small cramped bathroom without bidet (the only hotel room in Italy we have stayed in that doesn’t have one) and strange orange plastic hand wash basin.

That bathroom was humid and a fan automatically came on to ventilate it every 15-20 minutes or so, with a dull background noise that meant keeping the door closed.

We checked in just after the 3pm check-in time. The “suite” room was still being cleaned when we entered. The deluxe room had damp sheets that needed to be changed (and they were, very quickly on request). With an ungenerous 10am check-out, we came to the opinion that Matà was understaffed to tend to its 15 rooms.

We had to request the cooked breakfast menu after a 15-minute wait – we only knew it was available when we saw another table’s breakfast arriving from the kitchen. The scrambled eggs were, however, delicious. Overall the breakfast service was poor, verging on rude. After requesting a refill glass of orange juice, a half empty glass was slammed down on the table without comment! The hybrid “self-service” breakfast buffet was strange: guests were not allowed to help themselves to coffee and orange juice from the machines on the table next to the serve yourself buffet.

No one asked us how our stay was. Hopefully the hotel will revisit allowing guests to use the coffee machine and orange juice machine. Avoid the rooftop “suite” with hot tub, it’s incredibly poor value.

Without these disappointments we would have had a pleasant stay and considered it good value. Choose your room type wisely.

Pingback: Love Puglia: Top Travel Tips for 2025 - the Puglia Guys